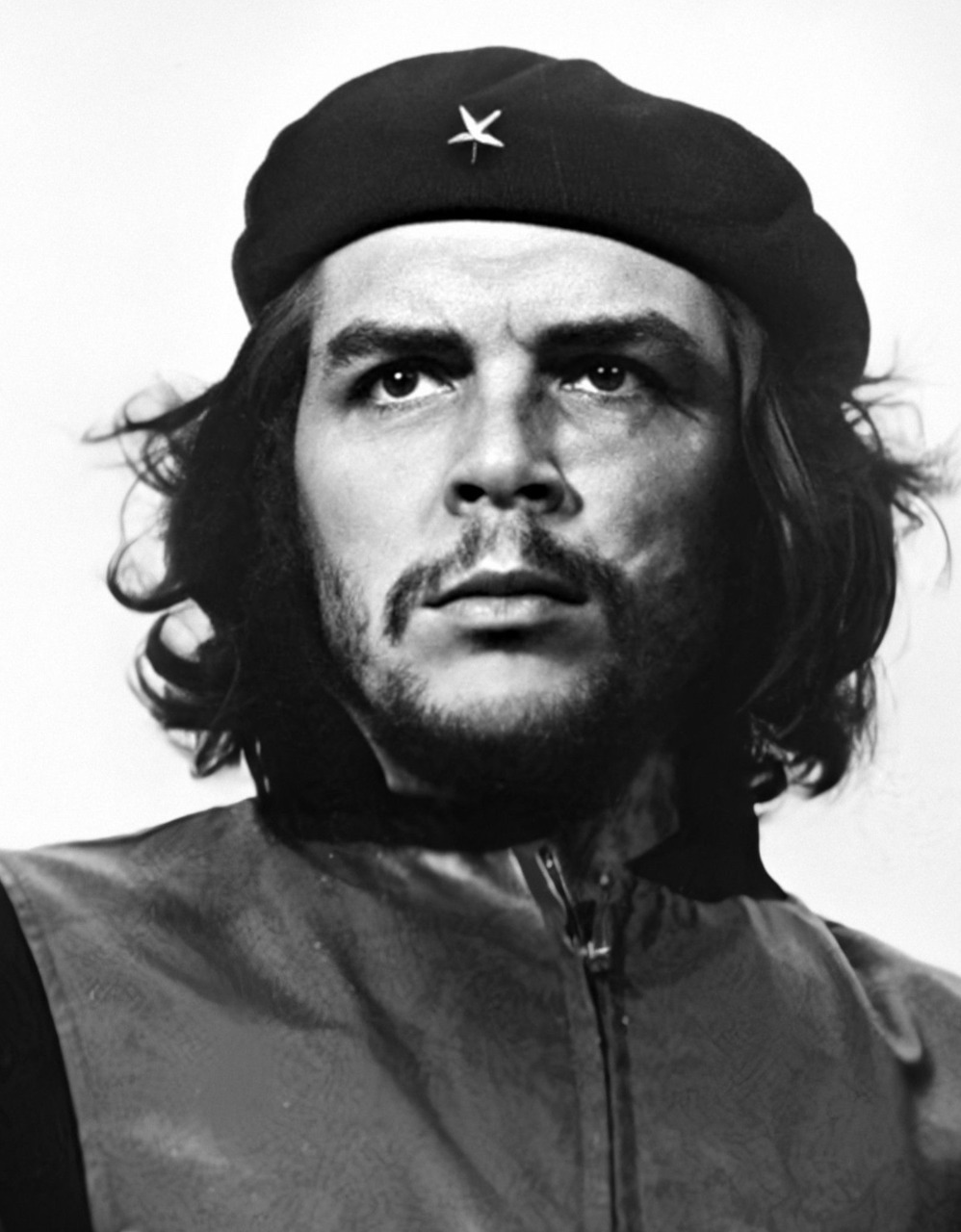

Che was murdered by the Bolivian military on 9 October 1967, 55 years ago. On this anniversary, we look at his continuing influence in Latin America.

‘At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality…Our vanguard revolutionaries must idealise their love for the people.

There is no life outside the revolution. In these conditions the revolutionary leaders must have a large dose of humanity, a large dose of a sense of justice and truth, to avoid falling into dogmatic extremes, into cold scholasticism, into isolation from the masses.

Each and every one of us punctually pays his share of sacrifice, aware of being rewarded by the satisfaction of fulfilling our duty, aware of advancing with everyone towards the new human being who is to be glimpsed on the horizon…The road is long and in part unknown; we are aware of our limitations. We will make the twenty-first century man, we ourselves.”

Socialism and Man in Cuba, 1965.

Ernesto Guevara.

Most people just quote the opening lines about love: I like to quote the rest of the passage as it says something about the intelligent austerity of the man, his humility, his acknowledgement of the tendencies of the intellectual elite to arrogantly detach themselves from the people, and his overwhelming commitment. This helps us understand why we still talk about the man 55 years after his death, it’s about more than an iconic image.

Probably the most striking testament to the role of Che in Latin American memory, and his continuing influence, came in June 2019 in Chile, shortly before the Estallido Social in October 2019 that led to the downfall of the Chileno neoliberal regime and the resurgence of hope across the continent.

The Chilean Lower Chamber of Congress voted on a right-wing proposal to have Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s accomplishments erased from school textbooks and to include instead alleged “war crimes” committed in the Cuban Revolution.

“The Chilean right seeks to distort the historical reality of our country and now the rest of the world,” Communist Party legislator Carmen Hertz asserted when speaking against the proposal taking the floor adding that "they intend to create a false tie between those who were supporters and accomplices of extermination policies and those who were its victims."

It was a heated debate and ended with defeat for the right, 70 votes against, 62 in favour and 12 abstentions. Right-wing lawmakers from the Democratic Independent Union (UDI), who spearheaded the idea, aimed to demystify Che's figure as a "hero of the left,” as many right-wing governments have tried to do so for decades. The fact that they even bothered to do so, in a country that seemed so settled as Chile prior to the Estallido is a testament to the continuing power of the Guevara example and his ability to still antagonise the right-wing after so many years.

Further evidence of this came in a meeting between Chile’s new leftish President Boric and Jon Lee Anderson, one of Che’s biographers, in June this year:

‘On the balcony, Boric searched on his phone for a poem: “Shocked, Angry,” the Uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti’s response to Che Guevara’s killing, in 1967. Standing amid friends and aides, he read in a theatrical voice, with a finger held aloft for emphasis: “One finger is / enough to show us the way / to accuse the monster and its firebrands / to pull the triggers again.”

Interesting that even someone as determined to look sensible and avoid the appearance of being a proper leftist as Boric should pull out and quote a famous work on the anguish of the writer at the death of Che.

Nearly every upsurge of revolutionary movements in Latin America over the last forty years contains traces of ‘Guevarismo' – sometimes explicit, sometimes glimpsed. In the view of indigenous rights activist Rigoberta Menchú, ‘In these present times, when for many, ethics and other profound moral values are seen to be so easily bought and sold, the example of Che Guevara takes on an even greater dimension.’

In Nicaragua, the Sandinistas, a group with ideological roots in Guevarismo though with a lineage going back much further, won re-election in 2006 and their supporters wore Guevara T-shirts during the victory celebrations

Bolivian leader Evo Morales has paid many tributes to Guevara including visiting his initial burial site in Bolivia to declare "Che Lives", and installed a portrait of the Argentine made from local coca leaves in his presidential suite.[In 2006, Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez who has referred to Guevara as an ‘infinite revolutionary’ and who has been known to address audiences in a Che Guevara T-shirt, accompanied Fidel Castro on a tour of Guevara’s boyhood home in Argentina, describing the experience as ‘a real honour.’

Guevara’s daughter Aleida also transcribed an extensive interview with Chávez where he outlined his plans for "The New Latin America", later the interview was released in book form.Guevara was also a key inspirational figure to the Colombian guerrilla movements, including the various FARC factions and the Mexican Zapatistas led by Subcomandante Marcos, himself a ‘Che-like’ figure. Also, the ‘expressions of the popular will’ that Che favoured over ballot-box democracy – neighbourhood courts and the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution – have found new expression in Venezuela and Bolivia.

Amongst the youth of Latin America, Guevara's memoir The Motorcycle Diaries has become a cult favourite with college students and young intellectuals.This has allowed Guevara to emerge as ‘a romantic and tragic young adventurer, who has as much in common with Jack Kerouac or James Dean as with Fidel Castro' according to Larry Rohter writing in the New York Times in 2004.

Jon Lee Anderson has theorised that Che is "a figure who can constantly be examined and re-examined, to the younger, post-cold-war generation of Latin Americans, Che stands up as the perennial Icarus, a self-immolating figure who represents the romantic tragedy of youth. Their Che is not just a potent figure of protest, but the idealistic, questioning kid who exists in every society and every time.’ (Quoted in the Larry Rohter article.)

There is something to all this about the timeless iconography, and the man as a symbol of universal rebellion who appeals to ‘questioning kids’ everywhere, but as ever bourgeois thought tends to the superficial. Che’s memory continues and resonates in Latin America because of:

Its continuing relevance to the concrete conditions in Latin America;

Its appeal to the spiritual consciousness of a continent upon which western materialism and individualism was an imperial imposition, not an organic development;

And the fact that the man had a lot of interesting and intelligent things to say, he was way more than a pretty face setting a bold and pure revolutionary example.

Wealth and Inequality

I wrote this in late 2019 when I was in Chile and took part in some of the demonstrations against the regime:

‘People across most countries were shocked when the riots kicked off: Chile was an OECD country, a stable democracy, the place that provided a model for development of the rest of Latin America etc etc ....Chilenos weren’t.

Chile is a rich country full of poor people.

While the country’s per capita income would give Chileans over $2,000 a month, most make $550 a month or less. A 2018 government study showed that the richest Chileans had an income nearly 14 times greater than the poorest. Chile is the most unequal of OECD countries, with an income gap that’s about 65% higher than the OECD average.

Now that’s not seriously high by Latin American standards, Chile has mid-range inequality by the standards of the region and many Chilenos are well-off compared to other people in South and Central America, but the fact the country enjoys such wealth and shares it so badly is the driving force behind the protests.’

In Latin America, the richest 10% of people capture 54% of the national income, making it one of the most unequal regions in the world

This recent blog post from the London School of Economics, not exactly comrades, states very clearly:

‘The region now needs to go beyond palliative solutions that target symptoms and instead attack the root causes. But how?

1. Focusing more on pre-distribution inequality;

2. Reducing commodity dependence;

3. Using industrial policy more strategically;

4. Going beyond conditional cash transfers given a paucity of production jobs;

5. Accepting that inequality leads to economic instability and social unrest.’

As we will see later, Che Guevara recognised many of these issues and started to work on them when he was engaged in the task of building socialism in Cuba after the revolution. Unlike the LSE and bourgeois economists in general, Che as a Marxist recognised that to effect the real and fundamental changes outlined above, it is necessary to remove the ruling class and deprive them of the wealth and hegemony that enables them to pursue their class interest. Che believed that this would take armed revolution and, given the intensity of the rearguard actions undertaken by the beleaguered capitalist class in Bolivia,with similar to follow in Chile and Brazil perhaps, it is easy to see why Che’s words and example resonate still.

Quasi-ReligiousAppeal to the Consciousness

Siles del Valle’s book, La guerrilla del Che y la narrativa Boliviana (1996) provides an interesting account of the ‘spiritual’ and psychological impact of Guevara. He explores Che’s concept of ‘the new man’ which he considers the ideological cornerstone of Che’s revolutionary praxis and an important source of inspiration for those who followed his example (See the opening paragraphs of this article for Che’s expression of how the new man should think and behave); del Valle compares and links Che’s vision of the new man and revolutionary love with the Christian body and theory of practice known as liberation theology that originated in Latin America in the 1960s. The book focuses on Bolivia and del Valle demonstrates how Che’s death, his concept of the new man, the ideals of the liberation theology and the political movements inspired by Che’s example influenced Bolivian popular literature an politics right up to the mid-1990s when the book was written. And now look at the advances being made in Bolivia.

When researching the article I noticed how often I saw people talking about ‘the example of Che,’ which reminded me of my own religious upbringing and people talking about ‘the example of Christ.’ This also reminded me of the words of the British politician and radio talk show host, George Galloway:

‘one of the greatest mistakes the US state ever made was to create those pictures of Che's corpse. Its Christ-like poise in death ensured that his appeal would reach way beyond the turbulent university campus and into the hearts of the faithful, flocking to the worldly, fiery sermons of the liberation theologists.’

,in a predictably hostile and arrogant article in 2007, also pointed out the power of the Christ narrative in ensuring the power and longevity of Che’s influence:

Whatever you think of Christianity or any organised religion, they have powerful semiotics and tell good stories that resonate, this is partly why they survive despite mountain ranges of evidence against their accuracy and consistency. And people admire toughness, purity of intent and a selfless lack of materialism: in a Latin America roiled by a murderous, rapacious capitalism and suffused with a religiosity borne from a meld of catholicism and indigenous beliefs, Che’s example and sacrifice will resound for many more decades.

Che, a Good Communist and Economist

Back to material affairs. Too many forget that Che spent a good few years after the success of the revolution engaged in the practical matters of building a new socialist society. He headed up the national bank for a while: the story goes that Fidel said in a meeting that he needed ‘a good economist’ to run the bank; Che thought he said ‘a good communist’ and put his hand up saying ‘that’s me!’ After some shock and laughter, he got the job.

Helen Yaffe from the University of Glasgow wrote an excellent book in 2009 about Che’s time building socialism in Cuba: Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution is a highly interesting and informative example of Che’s continuing legacy and one that deserves more attention. She points out that, inter alia, Che looked at institutionalising psychology as an economic management tool, set up nine research and development institutes including one for ‘green medicine,’ experimented with computerised accounts for industry formulated a new salary scale, promoted workers’ inventions and innovations, drove the mechanisation of agriculture, promoted the concept of work as a social duty and created an apparatus for workers’ management of industry. Many of these projects have evolved into major areas of activity and social organisation in Cuba today.

Yaffe points out that she was very aware of the ‘existential’ Marx, the man of the Economic Philosophical Manuscripts, he did not confine himself to hard economic analysis. She quotes Che from a 1964 interview:

‘Marx was concerned with both economic facts and their reflection in the mind, which he called a “fact of consciousness.” If Communism neglects facts of consciousness it can serve as a method of distribution but it will no longer express revolutionary moral values.’ Che felt that through the revolutionary process Cubans would transform themselves and this in turn would impact upon the institutions and relations they established within the revolution.

Che visited Yugoslavia and was impressed by various aspects of the self-management system there but described it as managerial capitalism with a socialist distribution of profits and pointed to the potential for competition amongst enterprises to to distort the socialist spirit. He also detected elements of managerial capitalism developing in the Soviet Union of the early 1960s, and forecast that this could lead to a return to capitalism.

Che made plans for economic diversification and rapid industrialisation that ultimately proved to be impracticable in view of the country's incorporation into the COMECON system. As early as 1965, the Yugoslav communist journal Borba observed the many half-completed or empty factories in Cuba, a legacy of Guevara's short tenure as Minister of Industries, ‘standing like sad memories of the conflict between pretension and reality.’ But Che was right, diversification and industrialisation were important, developing countries have to free themselves from many dependencies, including that upon the commodities cycle. See the LSE blog analysis referred to above.

Concluding Remarks

We end with a couple of quotes from Latin America, the first from Carmen a cuban nurse working in Vallegrande in Bolivia where Che’s body was laid out to view. Just behind that site, she worked in a clinic with 26 Cuban staff providing free health care to the community. The health programme was supported by a Bolivarian initiative and accord between Venezuela, Cuba and Bolivia. What Che was unable to do as a guerilla was now being carried out peacefully.

Carmen said: ‘Just imagine if he saw this. It shows his death was not in vain.’ Working seven days a week with hardly a break and far from her family, she said she received her ‘force from the Comandante.’

And finally, The Argentine/Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman said that Guevara's enduring appeal might be because;

‘to those who will never follow in his footsteps, submerged as they are in a world of cynicism, self-interest and frantic consumption, nothing could be more vicariously gratifying than Che's disdain for material comfort and everyday desires.’

¡Vive el Comandante!